Publicado por Nupul B´alam el 12 de agosto de 2006:

_

__In this post I will present some interesting objects and glyphic compounds I saw in recent publications or catalogues. Consider this as a little visit of a virtual exhibition. Lets call it “Bones and Incised Objects of the Ancient Mayas”. There aren’t a lot of objects presented, but I wanted to assemble here some of the more common and remarkable hieroglyphic compounds I saw those last weeks. Hope you’ll like it.

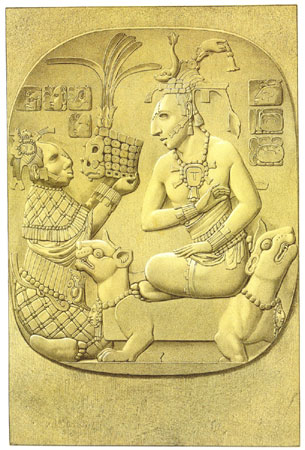

__The first object here presented is a bone that was once part of the leg of a jaguar (tibia). As David Stuart has shown (2005), the incised text clearly states that the bone belongs to a lady from Yaxchilan (lady K’ab’al Xook), but despite it belonged to her, it first belonged to a Jaguar.

Bone found in Yaxchilan (Drawing by David Stuart)

u-b’a ke-le B’ALAM-ma IX k’a[b’a]-la (XOK-ki…)

u b’aakel b’alam ix k’ab’al (xook…)

”This is the jaguar bone of Lady K’ab’al (Xook…)”

_

__David Stuart explains the –el suffix (b’aakel) as a “corporal”, “possessive” marker (2005: 58-59). We can find the same type of inscription on another bone photographed by Justin Kerr. This time, the jaguar bone belongs to Aj Tok’. This nickname/title (“he of the flint-stone”) was used by K’ahk’ Ukalaw Chan Chaahk, king of Naranjo between 755 and 780 (Martin and Grube 2000: 80-81).

_

_

Kerr file number 7747 www.mayavase.comu-b’a ke-le B’ALAM-ma a-TOK’-? SAK-CHUWEN? K’UH-‘NARANJO’-AJAW

u b’aakel- b’alam aj Tok’ Sak Chuwen K’uhul ‘Naranjo’ Ajaw

“This is the jaguar bone of Aj Tok, Ajaw of Naranjo”

_

_

Detail of K8019, www.mayavase.com edited by the author

__Another interesting type of inscriptions occurring on incised bone appears in the second example. The bone is labelled as u puutz’ (u-pu-tz’i). If we browse dictionaries we can find the following entries:

Yucatek: púutz’: needle (aguja) (Bricker et al. 1998: 222)

puuts’, puts’: aguja para coser, y puntada o punto de costura que se da con la aguja,

agua u otro licor o sangre de la boca (Barrera-Vasquez 1980 : 678)

Itza: putz’ : aguja (Kaufman 2003 : 361)

Mopan: puutz’ : aguja (Idem)

_

__David Stuart and Takeshi Inomata have interpreted this type of bone as “weaving bone” (200?: ?). Is has been argued so because of the recurring feminine ownership of this type of object, the weaving work being, in Mesoamerica, an activity restricted to women. It is interesting to note that the word b’aak (b'a-ki, “bone” in classic Maya) corresponds to “needle/aguja” in many languages (Q’anjob’al, Mam, Awatek, K’iche, Sipakapense, Tz’utujiil) (Kaufman 2003: 358). This may be due to the fact needles were made of bones.

__The word b’aak appears in a lot of incised bone texts, as u b’aak,”his bone”. Houston and Taube (1987) call this type of construction “name-tagging texts”. It mentions the name of the owner, or simply states that the object was the property of someone (in the examples below, of “Jasaw Chan K’awiil, Ajaw of Tikal”).

Tikal miscenalious texts n°181 and 44, Burial 116, Drawing by David Stuart and Christophe Helmke

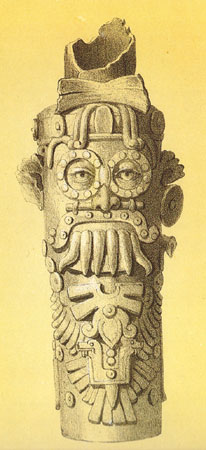

__The burial (n°116) of Jasaw Chan K’awiil provides another beautiful example of inscribed bone. The elected object is very famous. It represents the Maize god accompanied by several animals in a canoe. The Paddlers Gods here drive the canoe. In the text commenting the object and the image a remarkable glyph to be underlined:

Bone from burial 116, Tikal, Drawing by Linda Schele

u-‘CANOE’-B’AK ja-sa-wa ?-wa-ni 4-WINIKHAB tu-ma-ma

u ? b’aak Jasaw ?-waan 4 Winikhaab tu mam?

“This is the canoe-bone of Jasaw ?, 4 Katuns ancestor?”

__The bone is qualified of “canoe-bone” (see the paddle in the canoe-glyph in first position?). This term immediately recalls the representation incised on the object.

__Another term frequently found on incised objects is u jaach/jach:

_

u jaach b’aak Kaloomte’ From Dzibilchaltun

u jaach b’aak Kaloomte’ From Dzibilchaltun u jaach Copan Peccary Skull

u jaach Copan Peccary Skull

Looted bone, probably from Naranjo

Looted bone, probably from Naranjo

u jach aj Tok’ Sak Chuwen K’uhul ‘Naranjo’ Ajaw  Bone from Topoxte Island on Lake Yaxha, drawing by Stefanie Teufel

Bone from Topoxte Island on Lake Yaxha, drawing by Stefanie Teufel

u-ja-cha K’AK’-WE’-li/le CHAN-na-CHAK K’INICH-a-CHAK-chi[la] K’UH-AJAW OCH-K’IN-7-TAK u-b’a-ji-HUN-TAN-na K’UH-IX IX-‘CORD’-? IX-MUT-AJAW

u jach K’ahk’ We’el Chan Chaahk K’inihch ah Chak Chiil K’uhul Ajaw Ochk’in 7 Tak u b’aaj hun tan K’uhul Ix, Ix ?, Ix Mutul Ajaw“This is the incised bone of K’ahk’ We’el Chan Chaahk K’inihch, he from Chak Chiil, Holy Ajaw, West 7 Tak. Here it is the son of Holy Lady, Lady ?, Lady Ajaw of Mutul (Tikal).

_

__In the dictionaries, the actual equivalents of the word jach are translated as:

há’ach: to scratch, rasp, scrape (Bricker et al. 1998: 93)

hahrt’: a scraping (Stross on-line dictionary from Wisdom 1950)

in hahrti’ inte’ bak: I scrap a bone (Idem)

Hach: la desallodura hecha contra cosa dura, raspadura (Barrera Vasquez 1980 : 167)

_

__So the classical Maya word jaach is to be understood as jaach (b’aak), “incised, scratched bone. I thought a moment the term jaach could have described the function of the object, this compound appearing mainly on what looks like perforators, or autosacrifice bones. But the occurrence of the jaach word on the “Copán peccary skull” (see above) quickly destroyed this hypothesis. In sum, jaach really describes the way the text was realized (by scratching): "this is the scraped bone of X".

_BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barrera-Vasquez, Alfredo 1980

Diccionario maya Cordemex: Maya-español, español-maya. Mérida: Ediciones Cordemex.

_Bricker, Victoria et al. 1998

A Dictionary of the Maya Language as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press.

Houston, Stephen D. & Karl A. Taube, 1987 "Name-tagging in Classic Mayan script: implications for native classifications of ceramics and jade ornaments".

Mexicon 9(2):38-41.

_Kaufman, Terence, 2003

A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary, with the assistance of John Justeson. Downloadable at the URL: http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/index.html

Stross, Brian, Non dated,

Chorti Dictionary. Transcribed and Transliterated from Charles Wisdom’s (1950). On-line document: http://www.utexas.edu/courses/stross/chorti/

Stuart, David, 2005

Sourcebook for the 29th Maya Hieroglyphic Forum, March 11-16 2005. Department of Art and Art History, The University of Texas at Austin.

.jpg) Hola, buenos días

Hola, buenos días

u jaach b’aak Kaloomte’ From Dzibilchaltun

u jaach b’aak Kaloomte’ From Dzibilchaltun u jaach Copan Peccary Skull

u jaach Copan Peccary Skull Looted bone, probably from Naranjo

Looted bone, probably from Naranjo Bone from Topoxte Island on Lake Yaxha, drawing by Stefanie Teufel

Bone from Topoxte Island on Lake Yaxha, drawing by Stefanie Teufel